Get the latest articles delivered directly to your inbox!

Our Contributors

Class of 2022

Kyle Duke

Austin Foster

Charlotte Leblang

Ross Lordo

Class of 2021

Dory Askins

Connor Brunson

Keiko Cooley

Mason Jackson

Class of 2020

Megan Angermayer

Carrie Bailes

Leanne Brechtel

Hope Conrad

Alexis del Vecchio

Brantley Dick

Scott Farley

Irina Geiculescu

Alex Hartman

Zegilor Laney

Julia Moss

Josh Schammel

Raychel Simpson

Teodora Stoikov

Anna Tarasidis

Class of 2019

Michael Alexander

Caitlin Li

Ben Snyder

Class of 2018

Alyssa Adkins

Tee Griscom

Stephen Hudson

Eleasa Hulon

Hannah Kline

Andrew Lee

Noah Smith

Crystal Sosa

Jeremiah White

Jessica Williams

Class of 2017

Carly Atwood

Laura Cook

Ben DeMarco

Rachel Nelson

Megan Epperson

Rachel Heidt

Tori Seigler

Class of 2016

Shea Ray

Matt Eisenstat

Eric Fulmer

Geevan George

Maglin Halsey

Jennifer Reinovsky

Kyle Townsend

Join USCSOMG students on their journeys to becoming exceptional physician leaders.

A Different Kind of Ice Bucket Challenge

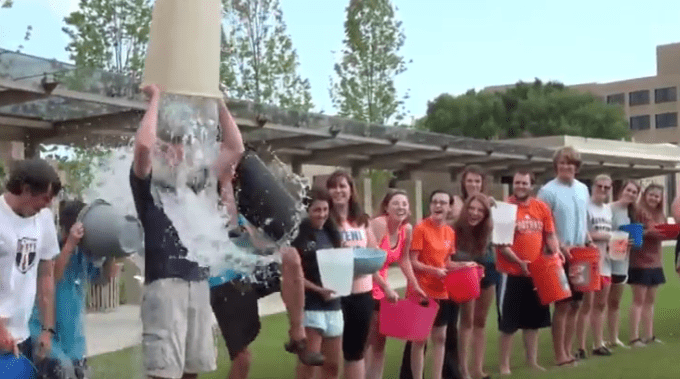

We’re nearing the two-year anniversary of that time when countless videos flooded your social media feed of people dumping buckets of ice water on themselves—the Ice Bucket Challenge, it was called—all to raise awareness for a disease called ALS, otherwise known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. You may have even participated in the challenge, as my medical school did. I remember the afternoon prepping for it. My inner junior-high boy came out in full force, trying to scavenge around the house for the biggest “bucket” I could find. Because, of course, if I was going to do this, I needed to do it right: with as much freezing-cold water as I could somewhat reasonably dump over my head. I searched the house high and low. I needed something big. “We’ve got a large mixing bowl in the kitchen,” I thought. Bigger. “I could use that cleaning bucket under the sink.” BIG. GER. “The trash can. Perfect.” Yes, I emptied (and cleaned) my trash can and filled it all the way with ice and water. Even threw a little salt in there to make it super cold. I lined up with my colleagues, and one-by-one in wave-like fashion we proceeded to pour the contents of our buckets over ourselves.

I don’t know how many of you out there have been foolish enough to pour an entire trash can of freezing water over yourself, but let me tell you, it is not a pleasant experience. First, you think you know what to expect, think you are ready. But then the water hits, and you realize very quickly you weren’t. For a millisecond, it sort-of felt like I was drowning after falling off a cruise-liner into the frigid Atlantic (here’s to you, Jack). My muscles went stiff, my breath stopped, my vision blurred, and an intense chill went down my spine, around Greenville County, and back up my neck until every hair I had was standing on end.

Even with the can emptied, the experience wasn’t over. I stood there cold and dazed, dumbfounded and numb, trying to make sense of what lapse of judgment made me decide a trash can was a good idea when a simple bowl would have sufficed. Eventually, though, the feelings subsided, the moment was over, and our awareness video was created. I enjoyed a good number of laughs and jokes with friends afterwards, completely unaware that these “ice bucket feelings” for ALS would not be my last.

Seeing patients in your clinical rotations during 3rd year of medical school shifts your perspective. Sure, we had learned about diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and even ALS in our textbooks. But no book can teach you like a patient can. Seeing their symptoms, hearing their stories, feeling their pain—it’s experiences in the exam room that your mind will never forget, and they often happen when you least expect them.

Several weeks ago on my neurology rotation, I had an experience like that. I was on my 2nd week of outpatient neurology and expected it to be much like my previous 6 or 7 days at outpatient clinics: take the patient’s history, do an exam, present to the doctor, and start again with the next patient. However, when I arrived, I realized that the neurology practice I was scheduled to rotate at that day was having its monthly ALS clinic. This meant all the patients we would see that day had ALS and would be seen by the more than 14 represented treatment groups who rotated from patient to patient (the doctor, physical therapy, speech therapy, etc.).

My colleague and I decided we would follow one patient (I’ll call him John) who was recently diagnosed. We would be able to see his treatment from each of the various teams’ perspectives. So before entering the room with the doctor, I went through in my head what I knew of the disease from my first and second years in medical school: “OK, it’s a neurodegenerative disorder, affecting both upper and lower motor neurons, which means we’re going to get mixed signs on exam. Got it. OK—typical presentation is muscle weakness, maybe trouble walking or swallowing, and eventually some respiratory issues. Poor prognosis, rapidly progressing, not much to offer in the form of treatment…OK. I think I’m ready.”

I wasn’t.

We entered the room with the doctor and immediately my eyes were drawn to the stretcher. Bright yellow and red, conspicuously standing in the middle of the room. Atop it, a man, not a year over 45, laid on his back and angled slightly upward. He was strapped down (presumably so as not to fall off) and attached to him was a clear tube; it went from his neck to a machine unseen behind him. He saw us coming in, but did not stir, nor did he utter a word when we greeted him. Instead, we were greeted by his present company, a large group of people—“It takes a village,” they say—and after exchanging the typical pleasantries, the cramped exam room went briefly silent, until the doctor asked the man on the stretcher, “How are you feeling today?” He moved his mouth, but no words came out. The only answer comes from the ventilator.

Pfffft. Pshh.

My heart sinks as my mind races with questions. What happened to this man? This is ALS? I thought he was just diagnosed? I knew it was rapidly progressing, but it can’t happen this fast, can it? My train of thought was interrupted by another question from the doctor: “Can you speak at all?” He shakes his head. No. Only the ventilator speaks.

Pfffft. Pshh.

The doctor addressed the family and we listened to the story. Apparently John had been dealing with some muscle weakness and pain in his legs for some months now. But he was tough and didn’t think it worth getting looked at. Just 6 months ago he was working full time. Now he couldn’t move anything except his head and eyes. Maybe his hands on a good day, but he was quickly losing control of those and could no longer communicate via texting as he had been doing. His voice was gone, and the nerves supporting his diaphragm were so weak that he needed a ventilator to breath. And just on cue…

Pfffft. Pshh.

As I listened, I stood there in a daze, overwhelmed by a mix of emotions. Heartbroken at his tragedy, but even more angry at my own naiveté. How could I think I knew anything about this disease? It was then that I remembered my Ice Bucket Challenge experience. How could I be so ignorant of this disease that I was supposedly supporting?

The doctor begins his exam, each passing question and response pouring another bucket of ice on this naïve medical student:

“Can you move your legs for me?”

Pfffft. Pshh. Nothing. My own muscles go stiff.

“How ‘bout your arms?”

Pfffft. Pshh. Barely a twitch. I’m having trouble breathing with the lump in my throat.

“What questions do you have for me?”

Pfffft. Pshh. An unrelenting chill goes down my spine as I watch the patient try to speak as best as he can to no avail. His family interprets:

“We read his lips now since that’s all he can do. He wants to know what can be done to treat him.”

“There’s only one medicine that’s been shown to extend life expectancy by a few months, but it wouldn’t be effective in his advanced case. I’m sorry to say there’s nothing we can do.”

Pfffft. Pshh. Silence. Tears.

I’m dumbfounded. I know the textbook says there’s no cure, but surely there’s something else, right? Right? Another bleak response, another bucket of ice. I felt cold…numb, even. Overcome by the feeling of helplessness toward this poor family. No, we don’t know what causes it most of the time. No, we can’t cure it. No, we can’t even slow it down. Bucket, after bucket, after bucket, drowning in a sea of tragedy and despair.

We heard the family speak about what it was like to care for him on a daily basis. Care is 24/7. Dressing, bathing, feeding—daily tasks that we don’t give a conscious thought to for one second in our lives now occupied every second of theirs, caring for their loved one while simultaneously managing his health needs.

My vision blurred as my eyes welled, but I could make out the singular thought behind every emotional face in the room: Why did this happen? Why weren’t there more answers? Why weren’t there more options? Why?

There’s something to be said, though, about the resiliency of the human spirit. Even in the most distraught of circumstances, joy—however brief—can be found. The medical team suggested the use of an eye gaze machine, which uses the patient’s eyes to type out words, as a means to communicate with friends and loved ones. We tried it out with John, and with some difficulty, he was able to get the concept and type out a few words, which he was excited about since he had not been able to text anymore. We set up an appointment to get the machine up and running at his home and took comfort in our small victory.

As we were concluding our visit with John and his family, his brother noticed John motioning with his head back towards the machine. “What do you want?” he asked. From his lips we could tell he wanted us to hold up the machine. John’s brother did as he asked. We stood behind the screen, puzzled as to what John was trying to accomplish. We had set up the appointment, and had confirmed it would work for him. What’s left to do? We peeked around the corner of the screen to see him shift his gaze towards the text-to-speech button. And for the first time in a long time, with a radiant smile on his face, John had a voice: “Thank you.”

With those two words and that one patient, I learned more about the true nature of ALS than two years of bookwork and one trash can could ever teach me. And it left me wanting to do more.

There are many things I cannot do in the search for answers for ALS, but there is something I can do. I can walk. So, on Saturday, October 22, my colleagues and I are participating in the Walk to Defeat ALS in Greenville, SC, a fundraiser that goes towards care services and research of ALS, under the team name “USC School of Medicine Greenville.” We’re beginning to see results from the fundraising efforts of the Ice Bucket Challenge, but there is so much more work to be done. Maybe there is nothing you can do to end ALS, but you can join us on October 22 in honor of my friend, John. And if you can’t do that, please consider donating to what is a very worthy cause. No, it’s not much, but it is something. And, though my interaction with John was brief, I have an idea of what he would say.

“Thank you.”

Formerly from the Baltimore area, I graduated from Bob Jones University with a degree in pre-med. Having interacted through MedEx with the faculty and students, I knew the doctor USCSOMG will graduate was the doctor I wanted to become. If I’m not hitting the books, you can probably find me spending time with my better half or on the basketball court. It is an honor and a privilege to be a member of the class of 2018, and I’m excited to share my passion for emergency medicine and health education with my peers. “To whom much is given, much more shall be required.”

Copyright 2021 USC School of Medicine Greenville