Get the latest articles delivered directly to your inbox!

Our Contributors

Class of 2022

Kyle Duke

Austin Foster

Charlotte Leblang

Ross Lordo

Class of 2021

Dory Askins

Connor Brunson

Keiko Cooley

Mason Jackson

Class of 2020

Megan Angermayer

Carrie Bailes

Leanne Brechtel

Hope Conrad

Alexis del Vecchio

Brantley Dick

Scott Farley

Irina Geiculescu

Alex Hartman

Zegilor Laney

Julia Moss

Josh Schammel

Raychel Simpson

Teodora Stoikov

Anna Tarasidis

Class of 2019

Michael Alexander

Caitlin Li

Ben Snyder

Class of 2018

Alyssa Adkins

Tee Griscom

Stephen Hudson

Eleasa Hulon

Hannah Kline

Andrew Lee

Noah Smith

Crystal Sosa

Jeremiah White

Jessica Williams

Class of 2017

Carly Atwood

Laura Cook

Ben DeMarco

Rachel Nelson

Megan Epperson

Rachel Heidt

Tori Seigler

Class of 2016

Shea Ray

Matt Eisenstat

Eric Fulmer

Geevan George

Maglin Halsey

Jennifer Reinovsky

Kyle Townsend

Join USCSOMG students on their journeys to becoming exceptional physician leaders.

To Love Our Patients

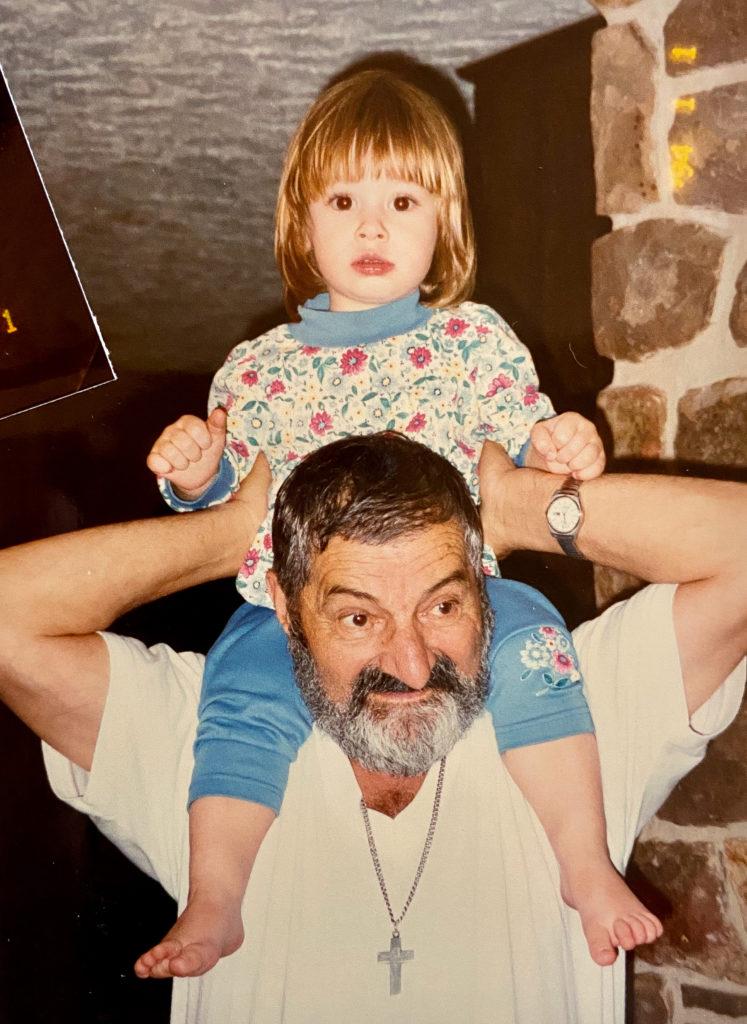

It started when I was young. My Papou (“grandfather” in Greek) had died. I remember standing in a line, surrounded by people in black, in a room that seemed oddly ornate. My Papou lifeless, yet full of strength, integrity, and compassion. He looked different in a suit, something I only saw him wear to church, where he would stand proudly, and loudly, in the first row. Instead, my memories of him included him wearing scrubs or an old flannel out on the farm.

Person after person came up to me, hugged me, and offered their condolences. The whole town was in that room. They’d tell me stories of him in the hospital, in a different role, and shared with me his wit. They’d tell me about his love for them, and how he had treated them like family. This went on for hours. So long, that my cousins and I snuck out to Sonic across the street.

This day didn’t mean quite as much to me as it does now. It was the end of a life and of a journey. It meant I wouldn’t see my Papou anymore. It meant he wouldn’t be able to touch the lives of those around him. He wouldn’t be the one holding the scalpel, cracking the chest, or saving the patient.

He was gone, yet he still lived. His legacy was, and is, alive and well.

I’d like to say that this is the moment that I decided to pursue medicine, because it’d be a great story. However, that came further on. All I knew is that I wanted to be like Papou. I wanted to be able to impact a community. I wanted to be remembered for my kindness and love, just like he was.

As I went through my hospital rotations, I approached each patient as not only a medical topic to learn about, but holistically as a person. I wanted to know about their families, how they met their partners, and even the pitfalls they had encountered. Each patient was a lesson, and I was a dry sponge ready to soak it up. The patients I followed weren’t just a diagnosis; they were family. I would make sure to be there when they needed to talk, wanted to learn, or when they took their last breath.

There’s a Greek work, φιλία (“philia”), which means brotherly love. Hence, Philadelphia being the city of brotherly love. I recently encountered a wise, Greek physician on the interview trail who reminded me of my own late Papou. He spoke of the different forms of love in the Greek language. Φιλία was unique, as it was the type of emotion that some feel towards their patients. As human beings, we crave connections and community. We gravitate towards those who care for us. In the end, we need each other more than we realize. By taking the extra second to hold a patient’s hand, sitting down to hear a story, or bringing them a crossword, we can exhibit φιλία . For a while, I saw this as a weakness, wondering why I had this drive to form these connections. However, doing this does not make me weak, but it instead makes me stronger.

So, it’s okay to love, and it’s okay to love strongly. We are put in a unique position in the medical profession where we are given the opportunity to reach so many. It isn’t something to be taken lightly, but to instead embrace fully. There is much more to the role of the physician than making the correct diagnosis and treatment plan. By embracing the importance of human connection in medicine, we can go from being great, to being phenomenal.

About the Author: Anna Tarasidis

Anna Tarasidis is a native of Greenwood, SC, and graduated in Bioengineering from Clemson University in 2016. You can most likely find her out on a hike, deep in some Netflix, loving on somebody’s dog, or, let’s be honest, in the library. She has a passion for people, whether by mentoring or teaching or just through a simple conversation.

Copyright 2021 USC School of Medicine Greenville