Get the latest articles delivered directly to your inbox!

Our Contributors

Class of 2022

Kyle Duke

Austin Foster

Charlotte Leblang

Ross Lordo

Class of 2021

Dory Askins

Connor Brunson

Keiko Cooley

Mason Jackson

Class of 2020

Megan Angermayer

Carrie Bailes

Leanne Brechtel

Hope Conrad

Alexis del Vecchio

Brantley Dick

Scott Farley

Irina Geiculescu

Alex Hartman

Zegilor Laney

Julia Moss

Josh Schammel

Raychel Simpson

Teodora Stoikov

Anna Tarasidis

Class of 2019

Michael Alexander

Caitlin Li

Ben Snyder

Class of 2018

Alyssa Adkins

Tee Griscom

Stephen Hudson

Eleasa Hulon

Hannah Kline

Andrew Lee

Noah Smith

Crystal Sosa

Jeremiah White

Jessica Williams

Class of 2017

Carly Atwood

Laura Cook

Ben DeMarco

Rachel Nelson

Megan Epperson

Rachel Heidt

Tori Seigler

Class of 2016

Shea Ray

Matt Eisenstat

Eric Fulmer

Geevan George

Maglin Halsey

Jennifer Reinovsky

Kyle Townsend

Join USCSOMG students on their journeys to becoming exceptional physician leaders.

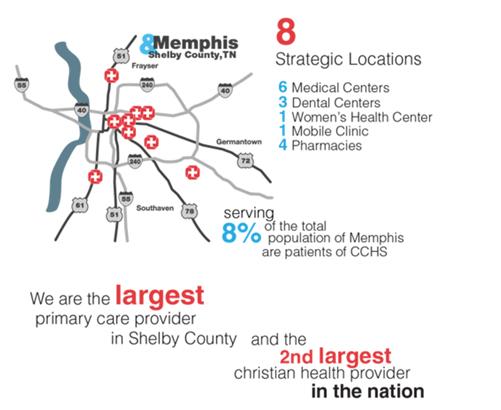

Summer At Orange Mound

This summer I spent two weeks in Memphis Tennessee. I did a two week rotation with Christ Community Health Services (CCHS). CCHS serves 8% of the population of Memphis, one of the poorest metro cities in the nation. In fact 92% of CCHS’s patients live below the national poverty level. Most of the 162,000 patient visits are with the uninsured or with those on Medicare/Medicaid. Christ Community goes beyond treating the underserved: CCHS believes they have the most impact on their patient populations when they live in the communities of their patients, and are active in their neighborhoods. Consequently, all the staff members of CCHS live in the different communities in which they work (there are 8 different clinics in 5 different neighborhoods). I lived in the neighborhood called Orange Mound. As a student, I rotated in the 8 medical clinics while practicing my medical skills and learning how to counsel patients in mental, emotional, and spiritual health.

Christ Community Health Services (CCHS) Infographics

As a student, I worked with physicians in the mornings. In the afternoons, I would work with spiritual health counselors. I was rather confident in my ability to take a patient history and do a basic physical, but when it came to talking to people about their everyday lives and struggles, I was terrified. When the counselors or I would go into a room we would say, “Here we care about your physical health, but also your emotional, mental, spiritual health. Is it okay if we talk to you about that?” Often the patients would say yes, and then we would proceed to a depression, anxiety, and other mental health screenings. From mental health we would then dive into the patient’s personal life a little more if they allowed it. As patients told us their stories, we could better know how to connect them with resources and encourage them. Sometimes that meant getting social services involved. Sometimes that meant just handing them a tissue and praying with them. Whatever the patient needed, we tried to meet that need. Many of the patients came from horrible social and economic conditions. I had no idea how I could relate and talk to them. For example, one afternoon the physician asked me to go and talk to a lady who seemed “sad”, but he did not have time to talk to her. I went in and began probing to see what was going on in her life. As I talked to her she told me how her boyfriend kicked her out of his house. She was trying to work but had a baby. Her family refused to care for the baby, and she was too poor to afford childcare. She cried because she wanted to get her GED, but did not know how. She felt trapped and was afraid. I did not know what to say and was afraid to sound cliché or cheesy. I just sat there, gave her Kleenexes, and would offer reassuring touch. I told her I did not have the answers, but we cared about her and would do our best to help. Later the patient said it was the best doctor visit she ever had. Through experiences like these I learned sitting, listening, and encouraging a patient can be more meaningful than solutions. Aspects of the counseling times were included in the patients chart. Things such as “Wants to apply to college. Follow up and give info on financial aid” or “Just divorced and needs a support group” were documented and considered important parts of building a relationship with patients. Through these opportunities I was able to see how important the care of the whole person is to one’s health.

On weekends or in the evenings, students worked in CCHS’s community garden or played with the local neighborhood kids. Everyone in the neighborhood knew about the medical girls on the corner. Neighbors would come by to have their blood pressures taken. Kids would want help with homework or band-aids (and popsicles). Even when we were too busy to play with the children, they would hang out on our front porch because they knew it was a safe place.

As I lived in Orange Mound, my eyes were opened to the struggles of a social class that I was unfamiliar with. Gunshots were fired on our street. The house on the corner was known for its drug dealing and prostitution. My belief that “anyone can make it if they work hard” was challenged. I saw firsthand how individuals are genuinely stuck in their condition: schools get low funding and poor teachers, so valedictorians get ACT’s of 18. Parents have to work several minimum wage jobs to pay rent, and cannot afford to go to school. I saw how the educational and healthcare systems have failed. I also saw nurses, physician assistants, office managers, doctors and their families fighting to better the broken systems. Doctors tutored high school kids and PA students gave up study time to babysit for free while mothers were working. Nurses teamed up with the local school system to push for changing the educational system. I learned how caring for a person’s health means caring for their physical ailments, but also crying with them or cheering them on as they get their GED. I learned that community gardens not only provide food, but also exercise and education. I learned that I don’t have to travel to a different country to find those who are in desperate need of care. My time in Memphis showed me a new way to practice medicine. A way that may result in a smaller house, lower income, and older car, but a way that I believe is richer because of the investment in the relationships with the people around you. I learned that sometimes you must lose to win.

Find out more about Christ Community Health Services at http://www.christcommunityhealth.org/who-we-are/

Anna Quantrille is second-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville.

Kristin Lacey

Copyright 2021 USC School of Medicine Greenville